Remarks by William Getzoff, past president of the Cliff Dwellers, delivered to a Joint Meeting of The Cliff Dwellers and The Chicago Literary Club April 14, 2003

Last year at the first of our joint meetings you may recall that Will Hasbrouck gave an excellent talk about the contributions to the Cliff Dwellers made by architects. This year, I would like to focus on a literary puzzle. Our Club was named after the novel The Cliff Dwellers by Henry Blake Fuller. Fuller however refused to join the Club and does not appear to have used it after it was established. Why did he refuse to join and what does this action tell us about the Club?

First, let me clear up a misconception. For those of you who have read Henry Regnery’s history of the Club, he quotes Charles Collins of the ChicagoTribune as claiming that the Club was not named after Fuller’s novel but instead was “intended to point a finger to the Cliff Dweller Indians of the Southwest.”

This is not correct. Hamlin Garland, who was the driving force behind the establishment of the Club, recounts a conversation he had with Fuller in one of his memoirs, Companions on the Trail. Garland told Fuller: “It isn’t a matter of ten years or your lifetime, Fuller, We are building something in this Club which will be alive and jocund when you and I are gone, and I want its name to be characteristic of Chicago and a reminder of you and your first fictional study of Chicago life.” “Nobody will want to be reminded of me.” Fuller responded. Garland dismissed Fuller’s comment and proceeded to name the Club after Fuller’s novel. As we shall see, Garland’s appeal to Fuller’s ambition shows that Garland never really understood Fuller but Fuller had taken the full measure of Garland.

Collins, however, was not altogether wrong in his emphasis on the effect of the Southwest Indian culture on the Club. The culture of the Native American Cliff Dwellers was of widespread interest in Chicago of the 1890s and had captured the imagination of many Chicagoans. Artifacts from the Southwest Indians were displayed at an exhibit at the Art Institute in 1891 as well as an exhibit at the World’s Fair of 1893. Both Fuller and members of the Cliff Dwellers shared a common interest in the Cliff Dweller culture. The opening chapter of Fuller’s novel, The Cliff Dwellers, is filled with Native American associations. Fuller makes a series of comparisons with the grim cityscape of urban Chicago and the natural beauty and majesty of the Cliff Dwellings of the Southwest. It is clear that the title of Fuller’s novel refers to the Native Americans of the Southwest.

The influence of the Southwest Indian culture was also deeply felt at the Club. “Kiva” is an Anasazi term for “male ceremonial chamber.” You pass by the John Norton mural of the Cliff Dwellers as you enter the Kiva. The Jarvie silver bowl, which currently is at the Art Institute, is based on a Navajo design. Ralph Fletcher Seymour, who is famous for having been Will Hasbrouck’s sponsor, designed the Indian motifs that appear on napkins and used to appear on the match books and china. Indian themes also played a part in some of the ceremonies used at the Club. Reading descriptions of these ceremonies now sounds like the inspiration for an episode from the Honeymooners when Ralph Kramden and Ed Norton attend meetings of the Loyal Order of the Racoons. The point is Fuller’s title reflected the same interest at the time in the culture of the Southwest Indians that is also seen at the Club.

So why did Fuller dismiss the honor Garland bestowed upon him and refuse to join the Club or even use the Club after it was established? Chicago at the turn of the century was well on its way to becoming the City on the Make. The basis for this observation comes from Carter Harrison’s autobiography, Stormy Years. You pass Harrison’s portrait as you walk down the hallway. Harrison was president of the Cliff Dwellers and gave the Club the gaur head which glowers down at you as you wait for the elevator. Both Harrison and his father were mayors of Chicago. Harrison served five terms. He was no machine hack. Educated in Europe and at Yale Law school, he was an early patron of Wagner. He describes the political scene as follows: “A rare conglomeration of city fathers ruled Chicago in the nineties, a great growing, energetic community, whose citizens for years from lack of interest, from supineness, from absolute stupidity, had permitted the control of public affairs to be the exclusive appanage of a low-browed, dull witted, base -minded gang of plug-uglies, with no outstanding characteristic beyond an unquenchable lust for money.”

It is the lust for money that was one of the theme’s of Fuller’s novel, The Cliff Dwellers. Fuller depicted the social status of the residents of the Clifton, the sky scraper which is the setting for the novel, as dependent solely on their income, making their status always precarious. Of course, Carter Harrison was not exempt from a lust for money. One of his detractors, Thorstein Veblen, from the newly established University of Chicago, created his theory of conspicuous consumption in his classic study, Theory of the Leisure Class, by a close examination of the vulgar rich in which category he lumped Carter Harrison. It does not appear that Thorstein Veblen was asked to join the Club nor does it appear that he expressed any interest in the Club.

Fuller found the chase for fame and fortune to be corrupting. He targeted anyone who he thought was on the make. In a short story by Fuller called The Downfall of Abner Joyce, he describes a character based on Hamlin Garland. The character develops a reputation for writing realistic and indignant stories of the rigors of life in the upper Midwest and strongly criticizes the monied elite for subjugating the rural poor. But then a funny thing happens. Abner Joyce comes to Chicago and is taken up by the same monied elite he condemned. He quickly abandons his earlier criticisms and becomes very pleased at becoming a fashionable figure and entering the world of the monied elite.

This speech is strikingly similar to the one Garland recalls giving Fuller on naming the Club after Fuller’s novel. Both Fuller and the hero of With the Procession reject the temptation to sell out their values for fame and fortune. It is unfair to characterize the personalities of the early members of the Club as motivated primarily by ambition and money. After all, they did accomplish much. Nevertheless, Fuller’s novels give some insight into what the early days at the Cliff Dwellers may have been like and why he refused to join.

Fuller expresses his discomfort with people on the make in another Chicago novel, With the Procession. An architect, Bingham, gives the following advice:

“Make your impression while you may. This is the time this very year. The man who makes his mark here today will enjoy a fame which will spread as the fame of the city spreads and its power and prosperity increases. You know that we are destined to be a hundred times greater than we are today. Fasten your name on the town, and your name will grow as the town itself does.”

Another tribute to the past is the Fireside Lounge area. Containing a current sampling of periodicals and fitted with comfortable furniture, this alcove is highlighted by the fireplace located in a wall covered with oak paneling, both having been installed intact from the original Club’s home, atop the nearby Symphony Center’s Orchestra Hall. That location, created expressly for the Cliff Dwellers, was its address from 1907 –1996. And during that span of almost ninety years the Club paid homage to the fine arts, ably led by a succession of officers and members that were to include author Hamlin Garland, publisher Henry Regnery, sculptor Lorado Taft, composer Leo Sowerby, and Frederick Stock, famed Chicago Symphony conductor. Today, that heritage continues. The Club now presents ongoing exhibitions of artwork, graphic design, and photography. Noon-hour talks are scheduled with a year-long series of early evening activities that range from book reviews to recitals to dramatic presentations.

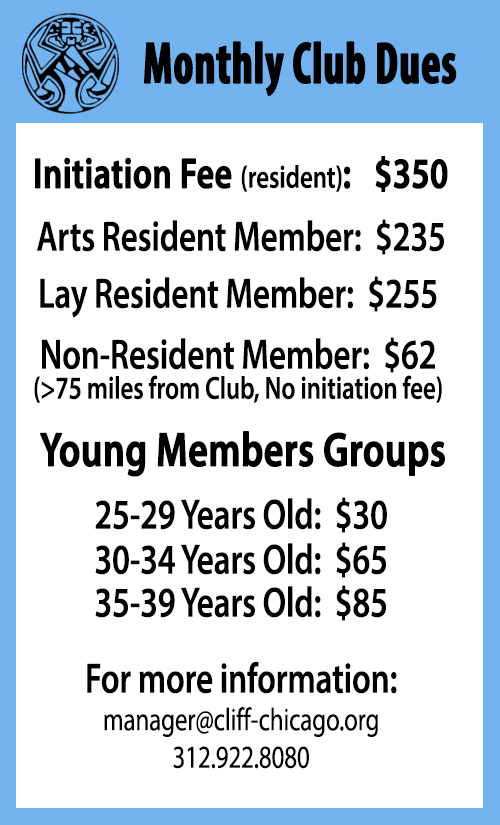

In its new home, twenty-two floors above the Michigan Avenue entrance to the well-known Borg-Warner building directly across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago and next door to Symphony Center, the Cliff Dwellers club continues to function as one of the city’s most honored establishments.

It takes to its heart those to whom the fine arts are intrinsic to daily life, acknowledging and enjoying the familiar while testing the challenges of the new. The Club is both a presence and a symbol. It exists to serve its members while it lends ongoing support to perpetuating the values that the arts provide, through patronage of local events and via funding by the Club’s own Arts Foundation.

When the Cliff Dwellers choose to honor an individual or an event, the members will rise to offer the Club’s familiar toast. To all who visit this sky-high aerie with its down-to-earth congeniality, as guests and as friends and, possibly, future Cliff Dwellers: Zivio!

About the time of Henry Regnery’s death in 1996, The Cliff Dwellers was required to find new quarters. We moved to the top of the next building north of Orchestra Hall (now Symphony Center). Chicago architect and Club member Larry Booth designed our new space with a vaulted ceiling and other aspects reminiscent of our old Kiva yet as current in concept as, in 1907, was the former location. The view is much the same as before, though from 13 stories higher.

AFTER THE FIRE OF 2001

It’s typical for the Cliff Dwellers clubhouse to be occupied by a member-sponsored private party on a Saturday evening, especially during the bleak winter months. And so it was on January 28, 2001. What made this one special was not the event itself, but the aftermath. Whether too many of the used table cleaning cloths wound up in the same refuse container, or whether some other combustible agent got accidentally mixed with them, or yet another circumstance—what is known is that a fire started during the early morning hours on Sunday, the 29th, when no one was present.

Technically, the fire itself was limited to the kitchen and connecting walls. Equipment either was rendered useless or was in a state requiring cleaning or repair. Unfortunately for the club, though, the greater disaster existed in areas beyond the kitchen. Smoke creates soot and on walls, the ceilings, and furnishings there was evidence of a fire by both a blackish film and a smoky odor.

What followed throughout the winter and spring months might well have been scripted from a Dickens novel or a dark comedy. Three insurance groups became involved in negotiating the cost of restoration and loss of business, and the consequent assignment of expenses. Decision-making came very slowly and, customarily, only after much prodding by an ad hoc legal committee created by the club.

Throughout the summer and early fall, work went remarkably smoothly and adhered closely to a firm schedule. It even was possible to include some modifications that enhanced club operations and appearance—such as creating a more convenient entrance to the supply room adjacent to the kitchen and improving airflow through new ductwork

A gala re-opening party took place on Friday, November 2, 2001.