Article by Ron Grossman noting the 100th Anniversary of The Cliff Dwellers.

Cliff Dwellers maintain 100-year-old love for arts

Top-floor private club still thriving

By Ron Grossman | Tribune staff reporter

November 25, 2007

The Cliff Dwellers’ windows frame the lakefront view Louis Sullivan saw while writing his memoirs in the Michigan Avenue dinning club during the 1920s. The father of modern architecture hadn’t had a commission in years and was living in a cheap hotel room lacking space, even for a drafting table.

Members of the Cliff Dwellers club, arts supporters who took their name from a novel that might apply to their top-floor recreation space, asked Sullivan to set down his thoughts on the art form he had done so much to shape. He did, describing the city’s potential as limitless.

At a time when Chicago’s other venerable private clubs are struggling, the Cliff Dwellers club is alive and well and enjoying its view. The Chicago Athletic Association closed its doors this year. The Tavern Club, which split off from the Cliff Dwellers in 1927, soon must vacate premises it can no longer afford.

“The defectors left because of a dispute over Prohibition,” Cliff Dwellers president William J. Bowe said of the split with the Tavern Club. “Both those who stayed and those who went wanted booze. The question was how to handle it.”

The Cliff Dwellers will celebrate their centenary Tuesday.

The club had the advantage of having Carter Harrison II, Chicago’s mayor in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, as a member. He reassured a jittery club president by saying that in Chicago, political influence outweighed the 18th Amendment. “The police will never interfere because of a little liquor that raises our spirits,” Harrison told the club.

At the time, the Cliff Dwellers club was atop Orchestra Hall, one door south of its present quarters on the top floor of the Borg-Warner Building.

The head of an Asian water buffalo Harrison shot still hangs on a wall at the Cliff Dwellers. The desk Sullivan used to record his thoughts on architecture is revered like an altar nearby. The two artifacts symbolize the twin foundations on which the club was built: culture and clout.

Harrison served a term as the club’s president, as did Frederick Stock, who was director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for much of the first half of the 20th Century. Bowe, the current president, is vice president and general consul of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Bowe reported that the Cliff Dwellers still extend a helping hand to worthy and impecunious artists. Through the artist-in-residence program, the club provides a kind of scholarship that gives seven artists membership privileges on the house for one year. In return, the artists are expected to put on a program for members.

Nora Williams, a violist, fulfilled her obligation by joining with a pianist to play a piece by Brahms twice. “First, we just played the notes as they were written,” said Williams, 40. “Then we went back, passage by passage, explaining and demonstrating how an artist develops an interpretation of a piece of music.”

That might not be much of a draw at other private clubs, where table-talk more likely centers on business affairs than aesthetic sensibilities. But Cliff Dwellers have always been different. There are no athletic facilities, no steam-room banter, no locker-room bravado.

The club was founded by a writer and carries the name of a novel whose author refused to join. In 1907, Hamlin Garland, a novelist with connections to high society, proposed a kind of clubhouse where the city’s artistic community could mix with businessmen with a taste for the arts. He was a close friend of Henry B. Fuller, whose novel, “The Cliff Dwellers” carried a poetic invocation to Chicago’s high-rise canyons and the entrepreneurial hustle that built them:

“Between the former site of old Fort Dearborn and the present sight of our newest Board of Trade there lies a restricted yet tumultuous territory … through which, during the course of the last fifty years the rushing streams of commerce have worn many a deep and rugged chasm,” Fuller wrote.

A bit of a loner, Fuller never joined the Cliff Dwellers, inspiring a lasting dispute over whether he deserves credit for the club’s name. An alternate theory has members analogizing their club high above Michigan Avenue to the American Indian cliff dwellings of the Southwest. Those favoring that hypothesis point to a long, rectangular recess in the ceiling, vaguely reminiscent of a kiva, an Indian meeting hall. In announcing the group’s formation Nov, 6, 1907, the Tribune took a third tack, pronouncing its quarters a “bungalow on a skyscraper roof.”

Its origins are hardly the only dispute the Cliff Dwellers have hosted. Passionate arguments on a rainbow of subjects are indigenous to the life of the club. Two tables designated “members tables” are open seating for anyone who grabs a chair and joins a free-flowing, often anarchic, discussion.

“I’ve had more intellectual conversations here than at a university,” said Deirdre McCloskey, a professor of economics, history, English and communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Joining her around the members table were two attorneys, two architects and a retired professor of philosophy.

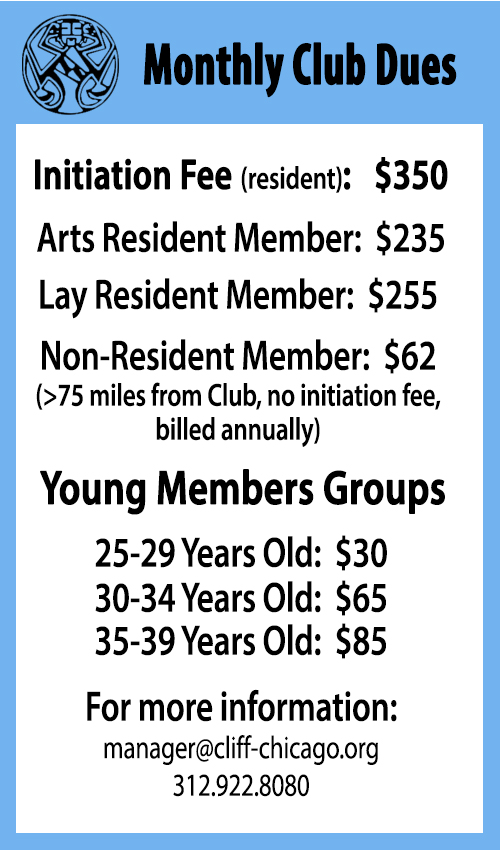

A daily conversational smorgasbord is virtually guaranteed by the club’s constitution: Garland provided that three-fifths of the 250 original members were to be drawn from the arts — painters, writers, sculptors, poets, musicians, architects, historians — the rest are the general public. The latter, designated “lay members,” pay monthly dues of $130; creative types get a discount rate, $110. There are about 400 members. The Cliff Dwellers’ rolls always have been heavy with architects, as befits Chicago, the birthplace of modern architecture.

Daniel Burnham designed the original club; Howard Shaw did the interior. Sullivan saw from the place a future for the city, for all its architectural sins:

“The Lake is there, awaiting, in all its glory; and the sky is there above, waiting, in its eternal beauty; and the Prairie, the ever-fertile Prairie is awaiting,” Sullivan wrote at his borrowed desk.

The present quarters were designed by Larry Booth, who is noted for his architectural renovations and remembers the heated arguments that accompanied the move into new facilities in 1996. “Some felt strongly our club would be out of place in a steel frame building,” Booth said. “They wanted a more traditional structure, like the Fine Arts Building, and that discussion continues.”

It is only fitting for a group dedicated to providing a place for high-brow concerns at the end of a business day. Garland, its founding president, once took poetic notice of what the club was about:

“Down in the city’s deeps we meet in savage fashion,

And play as best we may the selfish, sordid game,”

But after hours and up in the Cliff Dwellers:

“Man greets his fellow man, and only then remembers,

Art’s magic bond of light, and beauty’s bloodless stain.”