Perched atop Orchestra Hall, the Cliff Dwellers club has provided an informal refuge for artists, intellectuals, and eccentrics for almost 90 years. Now the Orchestral Association wants to bring it down.

Chicago Reader Oct 27, 1994

By Harold Henderson

There are 31 marble steps from the eighth floor of Orchestra Hall up to the Cliff Dwellers’ penthouse. Even when you’re alone on them, people keep looking over your shoulder. Old photographs and cartoons, along with faded telegrams and letters and menus with 35-cent entrees–in their frames they crowd the stairwell like paintings in a 19th-century art gallery.

Teddy Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson III need no introduction. Others do, though you hate to admit it–pianist Jan Paderewski, sculptor Egon Weiner, painter Albert Krehbiel. A few are as dated as antimacassars: actors John Drew and Otis Skinner, Civil War songwriter George Root. And–in a typical Cliff Dweller combination of formality and forgetfulness–a good many photographs on the stairwell depict people nobody can now recognize.

At the top of the stairs you turn right into the “kiva”–the clubhouse of the 350 Cliff Dwellers. Roughly 45 by 90 feet with an arched ceiling, it’s half parlor and half dining room (lunch and dinner weekdays, lunch only Saturdays). The wood paneling, dark floor, and heavy furniture might make it somber if it weren’t for the vista of Lake Michigan through the bank of windows facing east.

You can sink into a comfortable chair on the parlor side, but don’t be surprised if some of the stairwell people have followed you up here too–club founder Hamlin Garland looks down from his yard-square portrait over the fireplace; names of legendary figures like Frank Lloyd Wright and Jens Jensen appear on end tables. In this space Louis Sullivan wrote The Autobiography of an Idea, Vachel Lindsay acted out “The Congo” (“Boomlay, boomlay, boomlay, BOOM”) with such verve that a waiter fainted, and Adlai Stevenson III sought the most publicized quiet lunch in Illinois history.

The Cliff Dwellers is not like other private clubs, its members insist. Its dues are lower, it quit discriminating sooner, its atmosphere is friendlier, its focus on the arts (music, painting, sculpture, literature, architecture) is clearer, its “tacky elegance” is unique. But they quickly add that it’s like its fellows in one way. If separated from its relic-filled quarters–as per the current plans of its landlord, the Orchestral Association–it will probably die. “This space is not just some fungible, ordinary, run-of-the-mill leasable space somewhere,” club president Chester Davis Jr.–a real estate attorney in ordinary life–has written. “It is unique, and uniquely ours. It is our patrimony and heritage.” The camaraderie of these art lovers, it seems, is not portable.

Mounted high on the kiva’s north wall, and adding to its Edwardian-parlor atmosphere, is the head of a gaur, a big-game trophy brought back from Asia early in this century by Carter Harrison II. He later notified the club that he had passed it along to the Chicago Zoological Society. That was in 1935 and they haven’t been around to pick it up yet. “It never did belong here,” muses member Scott Elliott. “But it does now.” From the balcony on a clear day you can see Michigan–not to mention the lakefront from the Shedd Aquarium to Navy Pier, a view that guarantees good attendance for Venetian Night and July 4 fireworks. The balcony railing is chest high, wide, and solid. It’s also nine stories above Michigan Avenue, but that didn’t keep an exuberant Cliff Dweller from observing his 80th birthday by walking along the top of it.

The long-gone gentlemen who founded the Cliff Dwellers would be much more at home up here than down on the street. The kiva has no radio and no television. Nothing digital is in sight. The room is not air-conditioned; most members prefer the breeze. There is a grandfather clock on the south wall, next to the magazine rack, the chessboard, and the elegant-looking Indian pots. One recent visitor of the younger persuasion was heard to remark, “Boy, this place really is old. Who would want this?”

Scratch a Cliff Dweller today and you’re likely to find a self-professed history buff. But a century ago its soon-to-be founder was looking to the future. Basking in the afterglow of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, author Hamlin Garland puffed, “The rise of Chicago as a literary and art center is a question only of time, and of a very short time; for the Columbian Exposition has taught her her own capabilities in something higher than business.”

The Cliff Dwellers was one of many groups Garland joined or founded in hopes of turning Chicago from Porkopolis into Culturopolis. But by the spring of 1911 he was disappointed in his four-year-old club. It was supposed to have brought together Chicago artists and their patrons, and Garland was not charmed with either group. “The club fills up each day,” he confided to his diary, “but there are few men of any bigness or seriousness of purpose to be met there. I wonder when this town will begin to retain and honor its really creative men? . . . Chicago is only a big country town even now with its two millions of people. Our men in art are all feeling timidly or reflecting dimly.”

No doubt this was partly Garland’s depressive nature talking–he’d been worrying this subject ever since being drawn to Chicago by the fair–but he also knew that “small-town” was the deadliest insult one could hurl at Windy City culturati, because it was so true. “Our men in art” were mostly small-towners trying to make themselves over into metropolitan sophisticates. (“Men” was unjustified even then, given the presence in Chicago of poet Harriet Monroe, bookbinder Ellen Gates Starr, and theater director Anna Morgan, among others.) Like contemporaries such as Jane Addams and Edgar Lee Masters, Garland was a rural transplant in Chicago–and happy to be here. The engaging memoir of etcher, publisher, and founding Cliff Dweller Ralph Fletcher Seymour suggests why: “Why every one did not express their pleasure in the things and life about them by drawing, singing and dancing was unaccountable,” he wrote in Some Went This Way of his 1890s Indiana boyhood. “I felt sure singing was for showing that the singer was happy, something like laughing, and that drawing a cat or tree was like retelling a pleasant experience. But the others did not think so. They thought such forms of expression were exceptional, if not queer. It was reassuring to find evidence that artists and their work existed.”

But having escaped to Chicago, the art-minded found much the same ignorance and hostility, only on a larger scale. Benjamin Hutchinson, the legendary “Old Hutch,” offered a perfect example of the self-made Chicago philistine. Meat packer, banker, grain trader, and speculator who in September 1888 made more than a million dollars by cornering the wheat market on the Chicago Board of Trade, he forbade his son Charles to go to college. Charles obediently went into business in Chicago, but invested his money cautiously and his time in art (cofounding the Cliff Dwellers, presiding over the Art Institute from 1879 to 1924, and much more). When Charles in his lifelong quest for high culture bought a French painting of a sheep meadow, Old Hutch is said to have exclaimed, “Think about him! A son of mine! He paid $500 apiece for five painted sheep and he could get the real article for $2 a head!”

Those who preferred their sheep on canvas could at least find each other in Chicago, usually in the neighborhood where the Auditorium Theatre, the Art Institute, and Orchestra Hall clustered. A failed Studebaker wagon showroom at 410 S. Michigan became the “Fine Arts Building” and offered cheap rents and proximity. Here Seymour found a welcome and a studio; here a select group of men and women gathered as the “Little Room,” to talk, have fun, and drink tea after Friday orchestra matinees. (Its members, writes Bernard Duffey, were “Chicago’s best available substitute for a fully developed, leisured, and cultivated class.”) Here Garland and his brother-in-law, the sculptor Lorado Taft, and friends like Charles Hutchinson came up with the idea of a more sedate, men-only group. It was founded in 1907 as the Attic Club and soon reorganized as the Cliff Dwellers.

“The opening of this club has very real significance for the community of Chicago,” author and University of Chicago professor Robert Herrick told the January 1909 meeting in the kiva. “It means that those of us who are engaged in the practice of the arts, who are interested in the expression of our national life in something other than material accomplishments and mere efficiency, are to have a home.” Here refugees from small-town bourgeois and urban nouveau-riche philistines alike could befriend each other and practice the evanescent art of conversation.

Cliff Dwellers designed the kiva (Daniel Burnham did the exterior, Howard Shaw the interior), paid for the construction themselves–and agreed to pay rent to the Orchestral Association. None of the “gentlemen” involved then or later seems to have felt the need of a contract formalizing the arrangement. In its absence, the present-day Cliff Dwellers would like to believe that they own their clubhouse and hold some kind of ground lease from the orchestra. But there is nothing to show that they are not merely its tenants. Now that the Orchestral Association plans to expand into their space, the lack of “mere efficiency”–the Cliff Dwellers’ failure to obtain documentary proof of ownership–could doom the club.

The Cliff Dwellers’ name is a minor mystery itself. In 1893 Garland’s friend Henry Blake Fuller wrote a well-received novel, The Cliff-Dwellers, dealing with the conflict between culture and Chicago. He lightly satirized an 18-story skyscraper as an Indian encampment, with the building’s boilers a campfire, its cafeteria a tribal feast, its telegraphers and messenger boys the means of sending messages to neighboring chiefs. But Fuller himself never joined the club. A third-generation Chicagoan, he had less faith than Garland in the redeeming powers of art. “Cliff Dwellers” might well also refer directly to the southwestern Indians themselves, “picturesque Americans of the remote past,” wrote club member and Tribune columnist Charles Collins in 1947, “whose peaceful ways of life found expression in art work. For Indians, their cultural level was high.”

Club records give every indication of a serious Indian fetish. The club adorned its early yearbooks with southwestern designs. In 1911 its secretary formally acknowledged the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad Company’s gift of “five very fine large photographs of scenes in Colorado in the homes of the original Cliff Dwellers.” An early Harvest Home Dinner invitation read, “Happy now are the Cliff Dwellers for it is the season of song and dancing, of feasting and joy. Heavy hangs the golden corn . . . . Now shall each Brave paint for the Harvest Dance, now shall he tell his Squaw to purify herself and paint herself for the Harvest Moon.” If today this sounds archaic at best, founding member Ralph Fletcher Seymour thought it had “something of the very spirit of the club trapped in its words.”

Even the word “kiva” comes from a room the Pueblos typically devote to spiritual ceremonies. Unfortunately for white people taught to link spirituality with rising up, the southwestern tribes almost always built their kivas underground. Had Garland and company sought closer kinship with their namesakes, they could have leased the basement of Orchestra Hall rather than the roof. In the early 1920s the club’s aboriginal aspirations unexpectedly came to life when 20 southwestern Indians stopped by en route to Washington, D.C. (Accompanying them was John Collier, a social worker from the east who believed that Indian civilization demonstrated “the power of art” and “the fundamental secret of human life,” and who later became FDR’s commissioner of Indian affairs.) Their arrival came as something of a shock, according to Seymour, in part because “none of the Cliff Dwellers had any idea there were that many live Indians left, outside of the club membership.”

Nonexistent Native Americans were easier to sentimentalize. But the Cliff Dwellers coped. At lunch that day, wrote Seymour, “No one knew what they would eat or how they would eat it. The Indians could speak only Spanish and their native tongues. But they were very hungry and gobbled plateful after plateful, using their hands in place of forks. Pandemonium meantime swept through the building. The news that half a tribe of western Indians in full costume had come to the Cliff Dwellers spread through the neighborhood and then to the newspapers. The elevator men abandoned their cars, waiters gave up their responsibilities of serving the tables. The club members forgot they had ordered any luncheons. After the Indians had fed they wiped their lips on the back of their hands and Tony Romero produced an Indian drum. Jesus Maria Baca, Pablo Abieta, Juan Romero, and Santiago Pena raised their voices in a mighty chant and the other Indians arose and danced. Tables were upset, bank presidents climbed on chairs, broken dishes cluttered the floor and spectators crowded into impenetrable masses about the performers, as they rendered their Corn Dance for their Cliff Dweller brothers.” The “brothers” then passed the hat and raised several hundred dollars to finance the trip and a local Indian Rights Society.

The idea of a kiva as a place set apart for higher things appealed to Garland and his friends. Art and culture, they felt, could redeem Chicago from its daily round of grime and greed. As missionaries of culture, they tended to favor the orchestra and the Art Institute over more populist benefactions such as public libraries. The missionary image became literal in 1916 when Vachel Lindsay, a nonresident member, came to recite “The Congo: A Study of the Negro Race” (a poem almost too embarrassing to read even in private today), which rhythmically recounts how the god Mumbo-Jumbo is overwhelmed by Christian civilization.

Old Hutch might see them as fools or radicals, but most Cliff Dwellers were anything but avant-garde. In 1912, when Arthur Dove exhibited the first nonrepresentational paintings in the city, Bert Leston Taylor, a Tribune columnist and popular Cliff Dweller, “reviewed” the show in mocking doggerel (quoted by Ann Lee Morgan in The Old Guard and the Avant-Garde: Modernism in Chicago, 1910-1940):

Mr. Dove is much too keen

To let a single bird be seen;

To show the pigeons would not do

And so he simply paints the coo.

When the trailblazing modernist Armory Show came to Chicago in 1913, Lorado Taft denounced its artists as hypocrites and charlatans. Garland thought it unimportant “even as a joke.”

Art was supposed to be something special–and separate. In 1910 Charles Hutchinson presented the Cliff Dwellers with an exquisite silver punch bowl designed by member Robert Jarvie after the style of a Navajo basket. Garland responded with a prepared poem describing a magical western spring created by “Manitou, the mighty one,” to heal rival warriors, the “dark Comanche” and “vengeful Ute,” and concluding:

Warriors are we, but in another fashion;

Rivals for wealth and happiness and fame.

Down in the city’s deeps we meet in savage fashion,

And play as best we may the selfish, sordid game.

But here, at peace, before these glowing embers,

Meeting this ample bowl’s hospitable design,

Man greets his fellow-man, and only then remembers,

Art’s magic bond of light, and beauty’s bloodless shrine.

But even 80 years ago in Chicago, this was not the only way to look at art. Members of a slightly later generation took the lusty, brawling city to heart, embracing it in their work. Carl Sandburg’s “city of the big shoulders” may be a cliche now, but it represents a profoundly different attitude than do sacred springs and Taft’s idealized storytelling sculptures.

Sandburg, Edgar Lee Masters, and Sherwood Anderson “did not reject Chicago’s industrial and commercial life,” writes Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz in Culture and the City. “They exulted in Chicago’s scale and power. . . . Nor were the Art Institute and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra [let alone the Cliff Dwellers!] to set standards based on the great tradition. Such academic approaches were among the restrictions the younger artists were seeking to escape.”

In the end, all Hamlin Garland wanted to escape was Chicago. He moved to New York in 1916. Returning briefly in the 20s, he again deplored the city’s “intellectual halfway-house atmosphere. Its judgments are by men who have only advanced from Omaha or Sioux City or at best from some college and who are so sure of their opinions. . . . The Sandburgs, Masterses, and Hechts do not interest me.”

And yet, on top of Orchestra Hall, the avant-garde and the stick-in-the-mud, the world-class and the mediocre, all lunch at the same table. Arthur Jerome Eddy, who bought from the Armory Show, was an active Cliff Dweller. In 1917 he recommended former mayor Carter Harrison II for membership, in part because “he knows enough about sculpture to recognize as many figures in Lincoln Park as the average man, and he generously withholds his opinion of some of them.” Landscape architect Jens Jensen, a longtime Cliff Dweller, viewed nature much as Garland did art, and designed Chicago parks now considered worthy of painstaking restoration.

In the early 1920s, when the sick and frail Louis Sullivan was living in a closet-like room in a seedy hotel on Cottage Grove near 28th, the club came to his rescue. His architectural masterpieces–now recognized as such–had been forgotten or defaced, his iconoclastic opinion of the 1893 Chicago world’s fair (an “appalling calamity”) ignored. Sullivan could be difficult, he had no work, he had never been careful about money.

Two younger colleagues, Cliff Dwellers Max Dunning and George Nimmons, encouraged him to design a series of plates and to write his memoirs. The club “made him an honorary member and their rooms became his loafing and business headquarters,” as Ralph Fletcher Seymour recalled. “His meals [there] were free. It was there he used to do his writing, as afternoons slipped into evenings.” Seymour published Sullivan’s The Autobiography of an Idea shortly before his death. Years later, in 1947, Frank Lloyd Wright (who himself had briefly been a paying member) wrote the Cliff Dwellers: “I am pleased to be honored by the club that honored Sullivan. And I hope that I may occasionally warm his chair there. A fine thing the Cliff Dwellers did for him.” (In a more organized and less contrarian way, the member-funded Cliff Dwellers Arts Foundation today provides small grants to arts organizations.)

That bit of charity to a man generally considered a failure may be a good enough reason to describe the club’s quarters as “a kind of shrine of all that is excellent in the city’s artistic life” (as Cliff Dweller John McDermott recently did on the Sun-Times op-ed page). But less-than-high culture has always been on the program too. For every Robert Maynard Hutchins there’s a Roger Ebert, for every William Butler Yeats a William F. Buckley plonking on the harpsichord.

And then of course there are the parties. In the teens and twenties, Cliff Dwellers enjoyed an annual Dunes barbecue on the Indiana shores of Lake Michigan–a feast so gargantuan that Matthews, the club’s chef, had to load up two trucks the midnight before, according to Seymour, and then “drive to the appointed location, dig an enormous barbecue pit, erect tables and tents, cut tremendous quantities of firewood, plant sites for a couple of barrels of beer, prepare gargantuan piles of meat, chickens, potatoes, sandwiches and salad and try to be ready to receive the out-door-minded members and friends. About 2 o’clock buses and automobiles full of people and equipment, even train loads of participants arrived. Beer began to flow, the annual baseball game was played, excursions on foot, in canoes or boats were undertaken. Late afternoon hours were enlivened by amateur plays or pageants.” At sunset, “we all joined hands and to the pounding of Kurt Stein’s Indian drum danced a barbaric shuffle around the fire, . . . calling on the spirits of our dead Cliff Dweller brothers to break their sleep and dance with us.”

Eat your heart out, Robert Bly.

If that doesn’t sound enough like a men’s club, consider the year Seymour and a friend enlivened the bash by arranging a treasure hunt to be followed by an auction of the finds. The prime “treasure” was a cardboard carton, six feet by two by two, containing “one of the youngest, fairest, least experienced professional models . . . nude except for slippers, a girdle and a wreath of flowers on her hair.” They asked her to stay quiet until found and uncrated at the auction. Unfortunately, two elderly Cliff Dwellers happened by first, and sat down to rest on her half-buried carton. “After bearing the burden of their weight as long as possible she suddenly shrieked and tried to get out. This greatly surprised the two old men, and they fled.” She was eventually auctioned off after all, and “a couple of young Cliff Dwellers . . . pre-empted the car belonging to one of their fathers and drove back to town with their new possession.” In the same vein of this-may-be-art-but-we-don’t-think-so, after-dinner sketching of nude female models remained a Cliff Dweller tradition into the early 60s.

Strong drink joined the Cliff Dwellers only after the puritanical and autocratic Hamlin Garland left. It played a role in the final send-off for William Morton Payne, a club member so unassertive that he sat in the same place at dinner every night “and was miserable and restless when thoughtless or uninformed members pre-empted it,” wrote Seymour. “He was of frail physique and when the nation went dry he visited his physician for an opinion as to his probable life expectancy. Then he bought just enough good bourbon to supply him with one drink a day through that period and stored it in the club rooms. Unfortunately he did not last so long as his doctor had thought he should. A memorial dinner was given in his honor. A wreath was placed on his empty chair at the table head and his friends gathered in two long rows on either side. Before each was placed a glass similar to the one Payne had used, his stock of liquor brought from storage, the glasses filled and a toast drank to his memory, each man turning to the empty, wreath filled chair, raising his glass and saying, ‘Here’s to you, William.’ Toast followed toast until William’s bourbon was gone.”

Raconteur Seymour (who among many other things was the first publisher of Poetry magazine) lived to the age of 89, long enough to sponsor architect Wilbert Hasbrouck for membership in 1964–a connection with the club’s and the city’s past that Hasbrouck treasures. “I remember once someone asked Ralph, ‘Do you belong to the Lake Zurich Country Club?’ ‘Yes, I do,’ he replied. ‘In fact I’m the last surviving founding member.’ Then he got a faraway look in his eye. ‘You know, I’m the last surviving founding member of everything I’m a member of.’

“Ralph was a two-fisted drinker, but I never saw him drunk. He was run down by a car walking to his house early on New Year’s Day 1966. I always said to myself, that’s the way he’d want to go–a little drunk and after a good party.”

Over the years the Cliff Dwellers maintained a style combining public reticence and private bonhomie, and an approach to business at times suggesting that Robert Herrick’s denunciation of “mere efficiency” wasn’t just rhetoric. (The club also remained closely tied to the orchestra, with conductor Frederick Stock serving a term as president.) Even wealthy members like Hutchinson turned up on the list of those owing back dues. During the Depression allowances were made: when silversmith Robert Jarvie (creator of the punch bowl) tried to resign, pleading poverty, the board forgave his debts “on the condition that we see you at the Club more frequently hereafter. We need you and hope that you need us.” On this and other occasions the club seems more like an extended family than a formal institution with a nameplate on Michigan Avenue.

“The club hasn’t been very painstaking or fussy about what gets preserved,” observes member Scott Elliott, owner of the Kelmscott Gallery. “The big old library table–a lot of the old pictures were taken around it–was sent out to a repair shop and never came back, maybe some time in the early 1960s. Nobody can quite remember. The club has owned a lot of art over the years–it just disappears.” Even the decision to send the club archives to the Newberry Library was “very informal.” But, he adds, that very nonchalance “is one reason we value it.”

In at least one way the Cliff Dwellers have managed to be antiestablishment. Although the club was 100 percent behind World War I (something Jane Addams knew better than to endorse), in later years it disregarded the color line so sharply drawn elsewhere in the city. In response to a DePaul graduate student’s general inquiry in 1951, Edward Porter wrote, “One can bring a negro friend to the Club without bringing down the wrath of the powers that be.” John McDermott, founding publisher of the Chicago Reporter and now chairman of the club’s House Committee, notes that in 1971 it was the only integrated club he could join. (The club has had black members since at least 1967.) The all-male tradition died much harder, and before it did it dropped the club into the middle of the closest gubernatorial election in Illinois history.

Custom has it that celebrities can eat at the Cliff Dwellers without being mobbed; members recall seeing Richard M. Daley and Adlai Stevenson III talk things over there during Stevenson’s 1982 run for governor. That peace and quiet is no doubt what Stevenson had in mind that August 16 when he found himself having to explain to Sun-Times reporter Michael Briggs why he was still a member of a private club that wouldn’t let women join: “It’s very hard for me to find a place to have lunch.”

This didn’t go down well with those whose lunchroom is a Grant Park bench or McDonald’s. And the whole episode–with running mate Grace Mary Stern squirming and Stevenson reversing himself and quitting the club within a week–did nothing to dispel his indecisive image in a race he ultimately lost by the thinnest of margins. It didn’t do much for the club, either. “Stevenson belongs to the reactionary Cliff Dwellers Club, a group of dabblers in the arts” jeered a Sun-Times editorialist. “Some of its members probably have heard of Georgia O’Keeffe, Joan Sutherland, and Joyce Carol Oates, but they don’t consider them worthy of joining their club. (Not that they’d want to.)”

Two years later, under the presidency of Wilbert Hasbrouck, the Cliff Dwellers changed their minds. Part of the deal, he explains, was that ten women would be admitted at once, so no one would be first and no one would keep track of how many were members thereafter. Banker Yolanda Dean says the men “if anything, [have] bent over backwards to be welcoming,” though she acknowledges that for older members it took some getting used to. (Some are still getting over it: publisher Henry Regnery, the club historian, grumps in his 1990 book The Cliff Dwellers, “There is much to be said for leaving well established institutions as they are.”) Architect Gertrude Lempp Kerbis served as president in 1988-89. The club is “always friendly,” says former program chairman Evelyn Meine, who was in the first ten. “But you can’t try to make a sewing circle out of it. It’s a place where good guys can get together, whether they’re men or women.”

Ironically, the club has been losing artists even as it gains ethnicities and genders. In 1918 the Cliff Dwellers included 40 architects, 40 musicians, 35 writers, 26 painters, and 4 sculptors. In 1988, according to Henry Regnery’s 1990 history, it was down to 33 architects, 29 musicians, 7 painters, and no sculptors. Meanwhile, the number of “lay” members–especially lawyers–has risen dramatically. “This is fortunate,” writes Regnery, “for they have made it possible for the club to survive, but [this change] has undeniably changed the character of the club. Would the young musician . . . who later became director of music at the State University of Iowa have received the same ‘personal and artistic stimulus’ he speaks of if he had sat at a table of lawyers, or book publishers for that matter, instead of with Frederick Stock, Adolph Weidig or Bert Leston Taylor?”

Painter Robert Guinan, an active member, shrugs: “As Harry Bouras used to say, ‘Chicago artists don’t join,’ [probably because of] a misguided idea of the artist as a bohemian and an outsider, a real romantic kind of thing. My work means I’m essentially a loner, so I think it’s a nice relief to meet interesting people who know painting, movies, and music.” Attorneys can feel that way too. Assistant state’s attorney Leonard Foster says, “For some years when I was on the west side, the Cliff Dwellers was my window on the world–a chance to have an intellectual conversation at lunchtime. It’s like living in a college town.”

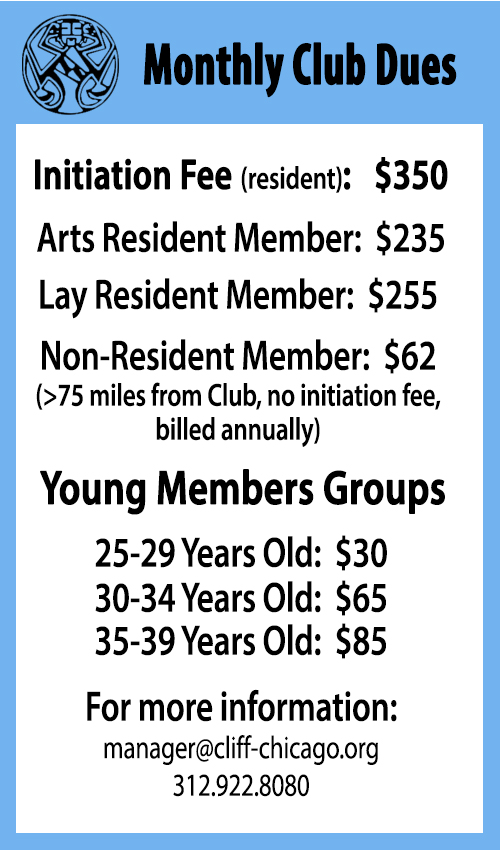

Why would anyone hesitate to join Ann-Arbor-on-the-lake? Some speculate the problem may be logistics (fewer people living and working downtown compared to 1909), or the perception of elitism (even though most current members insist that it’s the Cliff Dwellers’ lack of snobbery that keeps them coming back). It might even be the reality of elitism–initiation fees for painters and musicians now run $400, with monthly dues at $57 (members in architecture, literature, and lay professions pay more, those under 30 less). That’s just about enough to buy two dollar-a-day memberships on WBEZ. No “starving artists” here.

Or maybe the place just seems too conservative. It is hard to picture the Cliff Dwellers’ kiva–where Hamlin Garland’s portrait looks down upon lovers of jazz and Gilbert and Sullivan–in conjunction with exhibits like one upcoming at the School of the Art Institute, in which (according to advance publicity) “‘Frustration Machines’ use kinetics and are activated by the viewer. By kicking, punching or head-banging, the viewer is invited to create a hole in the gallery wall through a cushioned pad on the sculpture.”

If the Orchestral Association proceeds with its current plans, the question of new members may be moot after May 2, 1996. In a May 2 letter that club officials describe as a “bomb,” executive director Henry Fogel–himself a Cliff Dweller–gave the required two years’ notice to Cliff Dwellers president Chester Davis Jr.: “The Orchestral Association plans to create a private club for use by its major donors. . . . The space currently occupied by the Cliff Dwellers is the only workable location.” At a July meeting, Fogel reportedly indicated that the problem wasn’t just space. He saw the club’s proximity itself as a threat to the orchestra’s proposed donors’ room (a perception many Cliff Dwellers themselves find incomprehensible, given the close relation between the Lyric Opera and the Tower Club). Outraged members–just recovered from a traumatic 1990-92 lease renegotiation–have resorted to a letter-writing campaign, hoping to convince the Orchestral Association that it can provide a better donors’ space elsewhere, without “cannibalizing” another cultural institution or destroying the award-winning 1990 historic restoration of the kiva.

Fogel has said that he wants to reach a mutually beneficial agreement, but none has appeared yet. Neither Fogel nor Davis will speak for the record about negotiations taking place between the two groups–if indeed any are. One report has it that the Orchestral Association is proceeding to draw up plans to redesign the Cliff Dwellers’ space once they are gone. Many club members are bewildered at being treated this way. “Where is music in all this?” wonders Scott Elliott, lamenting how culture-as-business flattens everything in its corporate path. “Where else in this city than the Cliff Dwellers could such different people as Robert Jarvie and Charles Hutchinson, Bob Guinan and Henry Regnery, become good friends?” In a talk at a club reception October 21, he announced with bravado that he had just booked a table with the club’s manager for New Year’s Eve 1999.

President Chester Davis thinks all may yet be well if the club can get the Orchestral Association “to think not just about the bottom line and maximum dollar-per-square-foot return, but culture in a larger framework.” Yolanda Dean puts the same thought in a more combative way: “I think we’re up against hard business. We’re being victimized by the very kind of thing we don’t want to be a part of this club.” That is an adversary Hamlin Garland and Charles Hutchinson would recognize as easily as the kiva itself.